History

For generations, before the city, before the railroad, Big Lick was a series of salt marshes orienting East-West along a succession of springs that formed the tributary of Lick Run. Before the coal, it was salt that brought elk, buffalo and deer down from the mountains, and after them the Cherokee. This migration of game and man was the first, not the last, to seek out and find the rewards of the rich geological deposits in this fulcrum of headwaters north of the new river basin.

The Appalachian Highlands, a physiographic division consisting of thirteen provinces, ranges from 100 to 300 miles (160 to 480 km) wide, from the island of Newfoundland, South-West to the mountains of central Alabama. Today the purple mountains, still home to one of the most diverse deciduous forest systems in the world, seem gentle and low-lying with highest peaks little taller than 6,000 feet. If so the mountains hide their height in their age, and once would have stood more than 20,000 feet, high above the oceans and glaciers that defined life here more than 450 million years.

If it was salt that began Big Lick’s history of settlement, it was the Bituminous coal formed out of peat moss in the Ordovician period that made it last.

The French and Indian War wrecked most of the frontier settlements that had sprung up around these salt lands, and only a few stalwarts continued to call the area home. But Big Lick formed a natural junction along the Great Wagon Road (US Rt 11) traveling south down the Shenandoah Valley toward the Roanoke River Gap and the piedmonts of North Carolina, and so gradually more and more people began to move to the area.

In 1834, at this junction, the community made its first effort to become a town. Streets were laid and lots sold, and the little town of Gainsborough materialized. In 1852, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad built a depot at Big Lick. A few shops followed; in 1858 Isham M. Ferguson established a tobacco factory, a few years later a canning factory began operations. In 1871 Big Lick was chartered as a town, John Trout elected mayor; the council met regularly in Rorer’s Hall and erected a calaboose 12 feet square. Four years later The Big Lick News printed its first edition.

In 1881 it was noised abroad that two railroads, the Shenandoah Valley and the Norfolk and Western, were seeking a junction point. Then Rev. John C. Moomaw suggested that the council offer inducements to bring the terminal to Big Lick. He had arranged that a messenger convey to him at Buchanan in the morning details of the town’s offer. When the council promised a terminal and $10,000 to entice the railroad, Rev. Moomaw hurried on to Lexington to present the offer to Fredrick Kimball, then Chairman of the Norfolk and Western. In 1882 the junction was awarded to Big Lick.

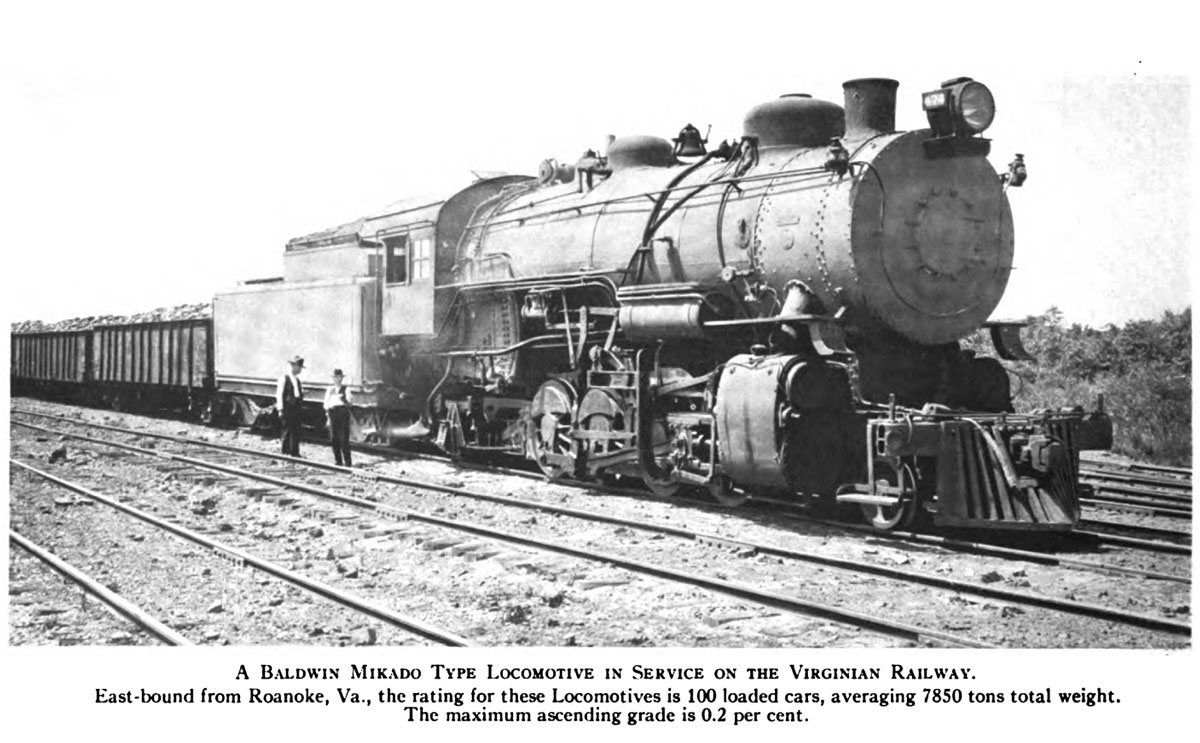

In 1882 the town changed its name to Roanoke and extended its limits. In 1881 there had been less than 700 inhabitants; in 1883 there were 5,000, and Roanoke received its city charter the next year. In 1906 the Virginian Railway came, bringing its shops and its great coal traffic.

Today Roanoke has a population of over 90,000 and, if we depend less on the railroad and coal, we depend more on the quality of life and environment that Big Lick continues to afford. Replete with history, rich in natural beauty; for all those who find Big Lick there are few who seek to leave.

Find Your Freedom, Without Leaving Home.

Experience downtown Roanoke living at its finest. Contact us to learn more!